Portraits of summer

The Time Is Always Now, Artists Reframe The Black Figure

The Box | Plymouth

Summer 2024 has seen a fantastic exhibition at the Box in Plymouth. Obviously nothing is better than seeing the work for real in the gallery, so go and see it before the end of September, but if you need it here are my highlights from ‘The Time Is Always Now. Artists Reframe The Black Figure’.

Shown over 2 sites, St Lukes and The Box, this show has works form 22 contemporary artists, all from African diaspora living internationally. One artist, Noah Davis passed away in 2015. The artists all depict black figures in their work and this show goes towards highlighting the absence of black figures in western art.

My visit began in the St Lukes Gallery, a converted church across the square from the Box’s main entrance. This space carries the reverence of its ecclesiastical architecture, setting the tone for a focused look at the work inside. The first work presented is by American artist Lorna Simpson, showing 2 large screen printed images of women from Ebony Magazine. These images have a layered effect that suggests obscurity and the multiplicity that occurs when screen printing. Both images are somehow both blurred and crisp, heightening the sense of a dreamy gaze. The green and blue hues wash the back of the images with the black dots of screen printing over the top. Each face is patched together adding dimension to each Woman’s persona. It makes me think about code switching and the social layers that are imposed on black women. This work was an accessible foreshadowing for what was to come through the galleries - a complex and rich showing of black lives.

Continuing through the space you arive at ‘A Midsummer Afternoon Dream’ by Amy Sherald. A large, vibrant painting of a woman and her dog collecting wild flowers. Her blue dress is rippling in the wind as she looks out to the viewer. It is fantastic. This life size figure holds the space in what is clearly a normal day for the subject. The bright but cloudy sky, white picket fence and dog in a bicycle basket show a simple pleasure, the ease of normal daily life, a dream life. Is this woman living this dream? Is this a normal afternoon for her? Or is she dreaming that this is her life? This painting points towards the infamous ‘American Dream’, an ideal long associated with the white nuclear family. A prescribed dream that fits a mould. This painting shows that the American Dream, whatever your dream is, can be as normal as everyone else’s. It is a space that can be taken up by black American women if they want, and by extension by any black woman. In essence this painting distills the feeling of safety within the subject, she seems at piece, her shoulders are out and she catches a rest leaning on her bike. The flowers she has picked show she has access to a garden, literally a place to grow. The dream may be that all women can have this feeling of freedom, freedom of space to exist with autonamy.

The curation of this painting furthers its thesis, hung on a black wall allowing the brightness of the image to shine out. The space above is lofty with day light peeking through 2 archways. In its self fantastical and dream like. Finally and by the artists own design Amy Sherald’s portraits are hung lower than the gallery standard. She wants the viewer to walk up and make direct gaze with the person she has painted without having to look up at them. She says “…the face is the most important part of the portrait and the eyes are the most relevant part of the face” [Amy speaking for Bloomberg Connects]. This allows the viewer to connect directly with her paintings and the people in them.

At the other end of the space directly opposite Amy Sherald’s flower picking cyclist is the only free standanding sculptural work in this space, Wangechi Mutu’s “This second Dreamer”. A highly polished bronze head laying on its side on a wooden block plinth on thin legs. Placed at the alter space in the former church, the piece is positioned as sacredly as can be in this space.

Bronze casting in art is very much associated with older, white, western male artists, and is held in high regard as a traditional, modern art practice. Of course art history also has examples of exquisite bronze work from West Africa such as those from the Kingdom of Benin and Edo in Nigeria but you have to a lot more research to find those and learn their histories. Wangechi has modelled this work on one by Brancusi. It is said that Brancusi, like other artists of his time took influence from African art forms as well as Native American and Oceanic island cultures. This sculpture takes back that cultural borrowing of an African figure an shows it on a “western” style object. This work is really beautiful, a good reason to enjoy a bronze sculpture. The smooth face and neck is highly polished, shining brightly with the features of the face standing out. The hair is left unpolished, showing the texture and darker finish of the braided hair. Having forgotten to read the interpretation for this work in the gallery, I later learned this is a self portrait, the artist committing her image to such a permanent material.

The next set of work at St Lukes that grabbed me was a series of paintings by Kerry James Marshall. I was instantly taken in by the dense blackness of the skin and the technique of acrylic paint on PVC. These works primarily show artists and we see some of them in their practice setting. A painter filling in a colour by numbers of herself and an artist probably making a mask. Although all of the paintings in the series (some not shown here) are exceptionally beautiful there is one that left me stunned - ‘Nude (spotlight)’.

A nude woman is lying on a bed with her hands behind her head. A dark blue bed sheet with a green lining is partially folded back covering only her legs as she looks out to the edge of the room with heavy eyes. A spotlight illuminates her, part of the bed and the wall behind her in an oval shape reminiscent of movie searchlights. The intricate floral pattern wall paper at the head of the bed transitions seamlessly from the light into shadow. The oval of light is crisp and neat. The light shines on her skin, describing her form while also highlighting the creases in the bed sheet. The complexity of this painting looks effortless, then you remember its acrylic on PVC, not, I imagine an easy process.

Heading across to the Box’s main building there are works in several spaces. The first work to come across as you head to the stairs for the main gallery is the second sculptural work in the exhibition. Thomas J Price’s ‘As Sounds Turn To Noise’, a large bronze sculpture in the former entrance hall for the Plymouth City Museum. This space has become The Box’s “Turbine Hall” - for lack of a better description. The space hosts large sculptural works that change with the temporary exhibition programme. The work in this space can be viewed from the ground and the balcony above allowing 360 degree views.

The large Bronze sculpture shows a solo woman standing with her hands on her hips with fingers pointing down, her eyes are closed. She wears comfortable atleasure and a pair of Nike trainers. She stands with both feet planted but her weight in one leg and as she takes a moments rest, her head is slightly tilted. It captures a momentary pause in her day, Quiet and thoughtful she stands, larger than life. She has neatly braded hair that is long and falls neatly down the length of her back. This work is a composite of many people. After a call out from the artists several people were interviewed, photographed and scanned. This work was put together as part of a wider project looking at what it means to be valued and represnented in society. This work is a direct link to the use of bronze within society and art history prompting the viewer to think about where they might normally experience the use of bronze.

A kin to the woman in bronze, people passing through this space are prompted to pause for a moment. Light fills the space from above as you look up at her face… Then, you carry on.

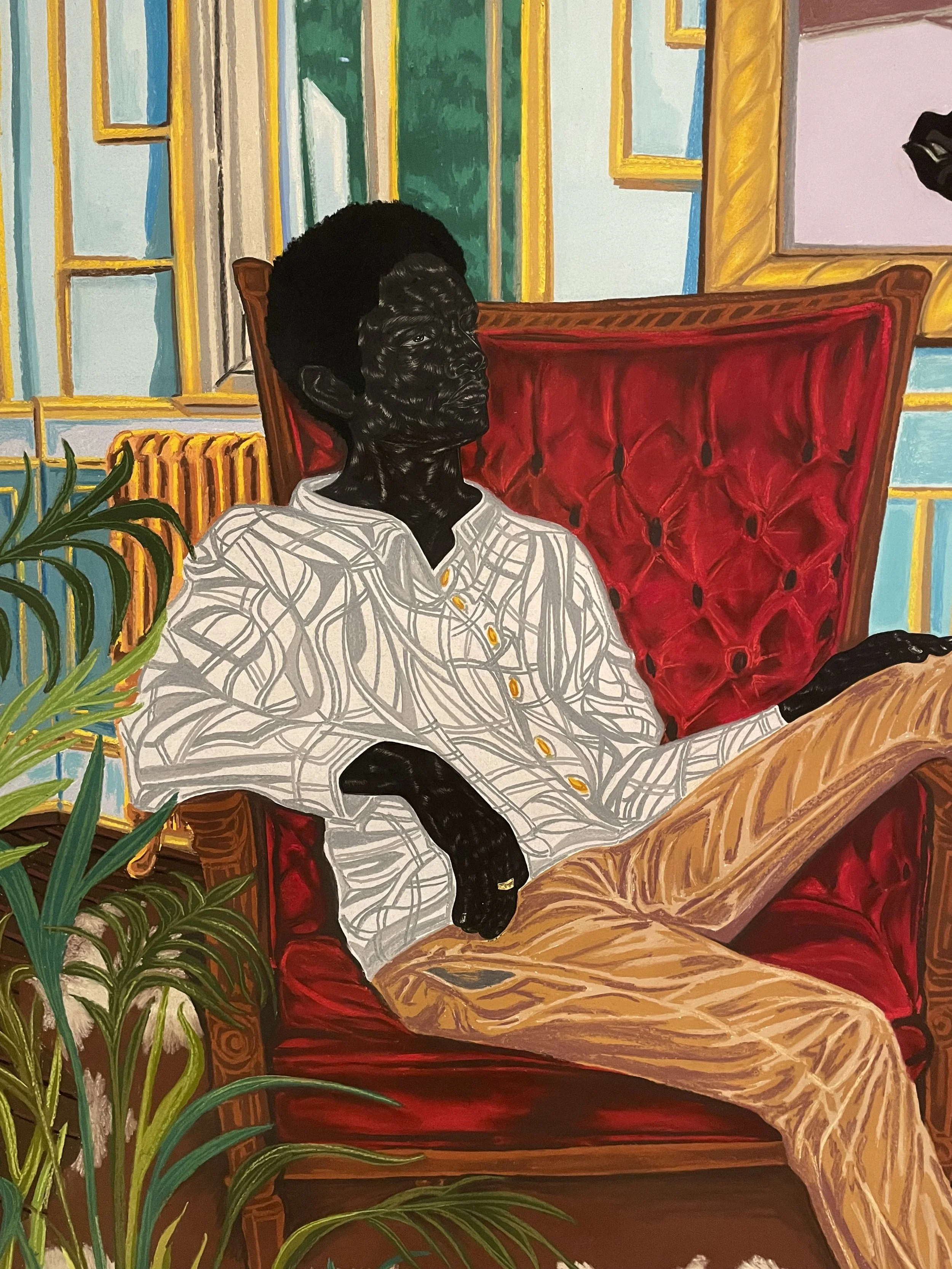

The next gallery, upstairs is filled with the largest paintings of the show. They fill only the perimeter walls of the gallery, the centre space only containing a few seats and the visitors. To the left as you enter is a series of 3 large paper works by Toyin Ojih Odutola. Made in charcoal, pastel, and pencil they are filled with texture, vibrant colour, close up and background detail. The scale of this work is super impressive.

They show the artist’s fantasy of wealthy Nigerian figures who wear fine clothes and sit in expensive bourgeois rooms. The fabrics in these works are full of rich texture and detail, the people’s skin have a silver shimmers over the sumptuous dark brown almost black skin tone. It speaks of a relaxed freedom of expression because the figures are comfortable in their space. These figures are imagined by the artist as she thinks about black freedom of sexual or gender expression, without confinement or judgement. [Curator Ekow Eshun explains on the Bloomberg Connect audio tour of the exhibition]. These works can keep you looking for a long time, there are framed images within in the scene that you just want to be nosey about. Some parts of the scene lead to other spaces through archways and windows that you want to peek through. All of that paired with the scale of the work transports you into that space. It’s possible to feel the airy rooms within as you begin to fantasise with Toyin Ojih Odutola. Her skill with the materials is masterful and utterly convincing.

Across the space is a duo of paintings by painter Hurvin Anderson. 2 striking images of people sitting in chairs with their back to the viewer. They look as though they are getting hair cuts with towels thrown over their shoulders, coming together at the back. I don’t know if I spent much time in front of these works but they have drawn me in retrospectively. Possibly the large blue sections framing the sitters interests me and the unusual format of showing them from behind. They leave me with questions that keep drawing me back to them.

The final space for The Time Is Always Now is in a smaller room at the back of the main gallery. The work in this space seems to be more referential, with well known figures from black activism and sport, plus work that is made using imagery from Old Masters Paintings.

On the far wall are a series of graphite drawings by Barbara Walker. In these works Barbara centres the black figures from Old Masters Paintings that would otherwise be the marginal character. Usually the marginal black figure is attending to the white figure in the centre. This re-focusing is achieved in two unique ways. In ‘Vanishing Point 24 (Mingard)’ the entire image is present with only the black figure, a young girl shown in detail. Skillfully marked onto the paper in black graphite she holds a shell in one hand and a vibrantly coloured piece of coral in the other. The rest of the image, the original centre of the piece, a white woman in a voluminous dress is only present in embossed form. She is pushed to the background leaving the young girl to hold the space as she looks up to a plant with a smile on her face.

In another work, Barbara Walker has drawn the entire image. This time highlighting the black figure by obscuring the rest of the image with a milky translucent Mylar film. A circle is removed where the young black girl peeks around the shoulder of a white sitter in a floofy dress. This work, through technique and the presence of a circle makes greater reference to the fringes of the image with the circle being bisected by the edge of the drawing. It makes the physical space taken up by the girl of very clear in proportion to the central figure.

In contrast to the previous galleries where the images were larger than life, imagined scenes and where the black figures take up the centre space, these smaller images show real life historically commissioned images. They make a great reference of what is real, in history and today, and what is dreamt of. Dreamt of by the black artists in this show, the black curator who pieced this all together and possibly by any black person or person of colour seeing this work.

This show teaches us some black history and shows us work by exquisite artists. It shows us black excellence, black pride, expression and joy. All things that have been absent from my own arts education. Luckily you can never stop learning and finding new work, being introduced to new artists and ideas or getting excited for others brilliance and success.

A couple of places I looked for further information.

The Time Is Always Now exhibition book | Bloomberg Connect App with words from the curator and artists | 4columns.org | The MET | Wikipedia’s page on Benin bronzes | Wikipedia page on Noah Davis